When Women Lost the Right to Vote, by Jed Quinn Peterson

When Women Lost the Right to Vote

The Minor v. Happersett Decision, 1875

By Jed Quinn Peterson

Introduction

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

These thirty-nine words, enshrined as the Nineteenth Amendment in the Constitution of the United States of America on August 26, 1920, represent the culmination of one of the greatest civil rights movements in our history. And while the year 2020 will see the rightfully celebrated one-hundredth anniversary of this watershed moment in American history, it is worth pausing to consider why this legislation was needed at all. Why were women kept for so long from participating in the electoral processes for local, state and federal magistracies? What political constructs, from the United States Constitution to English Common Law to state constitutions and even local laws, ensured that suffrage remained a male domain, and how were efforts to change this gendered notion of political equity rebuffed for so long, and by whom? And what does this story tell us about the very nature of citizenship and the rights and obligations that come with it? This paper will answer some of these questions, specifically focusing on the women’s rights movement of the post Civil War era.

Our starting point begins, perhaps unsurprisingly, with the unwillingness of the Founding Fathers to connect suffrage and citizenship together tightly. For a myriad of reasons, none less than that these men simply couldn’t believe that certain people deserved to participate in the electoral process, the Constitution as adopted was quite clear that it was the states that decided who voted. As each state wrote their own constitutions, that right (with the notable exception of New Jersey) was given solely to white men of a certain age who owned property. The new state governments privileged white people with citizenship, white men with economic and political rights, and wealthy white men with control over the entire system. This created a rigidly tiered hierarchy with just enough space to allow poor, talented white men the chance to climb the ranks but keep everyone else on the lowest rungs of the social ladder. The end result was a system that ensured the vast majority of human beings in the newly formed country did not vote. One of the great ironies of the American Revolution was the myriad of ways that new states embraced many of the injustices that induced the colonies to rebel in the first place. Perhaps nowhere was this clearer than in the case of no taxation without representation. The idea of representation is, at its core, a slippery one. In one sense, all representation is virtual. In a republican government, we give up our right to make our own decisions when we elect others to make them for us. Citizens don’t choose the direction the government takes. Elected officials do. And in this case, having a say in who makes those decisions is of the utmost importance. Freedom, at least in these limited terms, came from voting. Without participation in the electoral process, the people became subjects instead of citizens.

In an attempt to justify royal taxation in the colonies, the British government in the mid 1760s created the term virtual representation. They claimed that each member of Parliament represented all of Great Britain, not just the area they from which they were elected. As such, all citizens and colonists were represented by the government, even if they had no say in choosing the members of government. Americans such as Patrick Henry and Samuel Adams instantly attacked this new philosophy, arguing that virtual representation was not representation at all and that they would not pay taxes to the crown unless they were permitted to elect the leaders guiding the empire.

And yet, after the Revolution was won, most of those leaders who had fought to expand suffrage to all citizens came to believe that their experiment in republican government would only succeed if certain members of society remained represented virtually. Children, of course, have never been considered responsible enough to vote. Slaves were left off the voting rolls. Women. The propertyless. All sorts of religious groups. Native Americans. It was a very lengthy list. And yet, even beyond the massive amount of people left out of the political process, men who met all the prescribed requirements found themselves represented virtually as well if they chose the losing candidates. They were not represented in government either. For all the anger focused on the injustices of virtual representation, in the end only a ridiculously small fraction of citizens voted for those in power and were actually represented.

The story of America has been, therefore, the plight of different subsets of citizens fighting for actual representation rather than virtual representation through access to the vote. The first changes occurred in the early 1800s as the nation became industrialized and massive numbers of immigrants flooded in. By the 1840s every state had discarded property requirements to vote. Age limits were lowered. Citizenship requirements were lessened. And yet, as the numbers of individuals voting increased substantially, suffrage remained almost exclusively in the hands of white men. It would take amendments to the Constitution to ensure that race and gender were not used to keep people from voting. While changes assuaged portions of the population that demanded representation, none of them challenged the intrinsic belief, codified in our highest laws, that citizenship does not guarantee representation through voting.

That isn’t to say there haven’t been attempts to forge a connection between citizenship and suffrage. Perhaps the best chance to make the case that all citizens had the right to vote came in Minor v. Happersett, decided by the Supreme Court in 1875. After wild shifts in composition and numbers caused by the Civil War and Reconstruction over the previous fifteen years, the Supreme Court was settling in under new Chief Justice Morrison Waite. While the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments had created opportunities to look at old customs and new ideas alike, many men in power fought to keep the country from shifting to far in the direction of new social norms. And one of those norms they were not about to let go of easily was that voting was a man’s purview.

The Election of 1872

Our story begins, as so many in American history do, with an election. The election of 1872 remains one of the least discussed in our history, yet it was a wild and telling affair. The race pitted Republican President Ulysses S. Grant, whose administration had been rocked by scandal after scandal, against Horace Greeley, the surprise candidate of a disparate group of radical Republicans and Unionist Democrats united solely by a hatred of the sitting president. Grant won the popular vote, and when Greeley died a few weeks before the Electoral College met, his votes were divided up, giving Grant an easy victory and four more years in the White House. Despite all the insanity surrounding this election, in the end nothing really changed.

President Ulysses S. Grant

What made this election unique beyond all the other twists and turns was that it was the first presidential election held after the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, ending slavery, the Fourteenth Amendment, promising civil rights, and the Fifteenth Amendment, granting suffrage to former slaves. Many believed these changes to the government opened the door for a reinterpretation of who was allowed to vote. The Fourteenth Amendment, while bringing the word “male” into the Constitution for the first time, and while commonly understood as passed specifically to overturn the Dred Scott decision, was vague enough that many believed it connected citizenship and suffrage in a new way, which would have allowed women to vote. The section that lead many to believe this new amendment could be used reinterpret the relationship between suffrage and citizenship read;

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

If men were citizens and they could vote, then women who were also citizens, should be able to vote. Numerous women’s rights groups joined together in the election of 1872 to advocate for this very interpretation. It was a stretch, to be sure, but the only real chance at that moment of winning the right to vote. And so women went to registration booths and voting places throughout the nation, hoping either to vote or be restrained in such a way that they could sue for the right in court. While this movement involved thousands of women, the most famous case resulting from this effort was the trial of Susan B. Anthony.

The Trial of Susan B. Anthony

Susan Brownell Anthony was born in Massachusetts in 1820 to Quaker parents who believed in the abolition of slavery. After connecting with Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1851, with whom she would co-found the American Equal Rights Association, she began touring the country speaking on behalf of female suffrage. The two eventually founded the National Woman’s Suffrage Association, which became a leading voice calling for female suffrage through amending the Constitution. In 1872, however, they had another thought in mind.

They were just going to vote and see what happened.

Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

The story of what happened next is well known. Anthony arrived at the voter registration station, expecting to be turned away, but somewhat surprisingly was allowed to register. The men in charge were unsure of the legality of adding her to the voting roles, but felt it better to err on the side of allowance. They were the only registrars in that election year to come to that decision, as everywhere else men in charge of registration turned female voters away. Election Day arrived, and once again Anthony was allowed to participate based on the indecision of those in charge. It is fairly certain Anthony expected to be turned away, but when she was allowed to vote, she, along with fourteen other women accompanying her, jumped at the chance. Their votes were insignificant in the total tally that day, as Grant won in a landslide, but the principle of the thing mattered.

And it made some very powerful people very angry.

Anthony was arrested shortly after the election, and her trial was fast-tracked up the system. As talented and organized as Anthony was, she was no match for the forces arrayed against her. The justice, who had never served as a trial judge before, had already decided upon the guilty verdict before the trial began. He refused to let Anthony testify during the trial, and when the jury went to deliberate he informed them they must deliver a guilty verdict. He did all of this, as he would later say, so that “there would be no misapprehension about my views.”

The kangaroo court was the worse kind of farce, but the injustice didn’t end there. Anthony was fined one hundred dollars for voting illegally, roughly two thousand dollars in today’s money. Channeling the long history of civil disobedience in this country, she refused to pay the fine, expecting they would arrest her again and she could take her case to the Supreme Court.. The judge deliberately refused to give her the satisfaction of arresting her for non-payment, however ensuring she would be left without a path to the Supreme Court.

In many ways, Anthony’s court case mirrored the election of 1872: Much Ado about Nothing. All that time and effort and speeches and movement and divineness, and in the end, nothing changed. The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments had been safely protected and the efforts of women to vote squashed. Out in Missouri, however, another woman and her husband had taken a similar approach during the election of 1872, only she had found a way to push her case all the way through to the Supreme Court.

Minor v Happersett

Virginia Louisa Minor was born in 1824 in Virginia. She married her cousin, Francis Minor, in 1843 and eventually settled in St. Louis, Missouri before the Civil War. In1867 she was elected as the first president of the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri and in 1869 the Minors began a campaign that the Fourteenth Amendment, beyond its other aspirations, had given women the right to vote. According to the Minors, since women were full citizens they were entitled to all the benefits and immunities that citizenship brought with it, meaning they already had the right to vote. Since the constitution lacked anything specifically saying women couldn’t vote, by agreeing that all women were citizens, the thesis hinged on whether or not voting was one of the fundamental rights of citizenship. If it was, women should vote.

Virginia Minor

Expecting to be turned away as Susan B. Anthony had, Virginia Minor attempted to register to vote on October 15th, 1872 in preparation for the upcoming general election. Unlike Anthony, who was arrested and charged with a crime for voting, Minor was simply turned away. Since married women weren’t allowed to sue in court, her husband, Francis, brought suit against the man who had blocked his wife from voting, Reese Happersett. Francis Minor claimed that the Constitution “nowhere gives [states] the power to prevent” anyone from voting. It was an argument of negation, but lesser arguments had been successfully argued in front of the nation’s highest court.

The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case on February 9th, 1875. Francis Minor led the presentation, the crux of his argument that denying the right to vote had been a practice rather than a law in the states. Minor detailed the twenty year period in the late 1700s and early 1800s when women in New Jersey had voted before adding that,

"the plaintiff has sought by this action for the establishment of a great principle of fundamental right, applicable not only to herself but to the class to which she belongs, for the principles here laid down extend far beyond the limits of the particular suit and embrace the rights of millions of others, who are thus represented through her. . . . It is impossible that this can be a republican government, in which one-half the citizens thereof are forever disenfranchised."

The state of Missouri was so confident that the court would agree with their position that they didn’t send lawyers to argue in their defense. They knew the burden of proof was on the Minors and that it would have been nearly impossible for the justices on the bench to find that Happersett was at fault. As Francis Minor finished his oral argument, he must have looked across the chamber, hoping to find just one judge who might agree with them and perhaps sway the others. It’s hard to imagine he felt much in the way of encouragement, however, as a brief examination of the nine men challenged with answering this vital question left little to wonder how they would vote in the end.

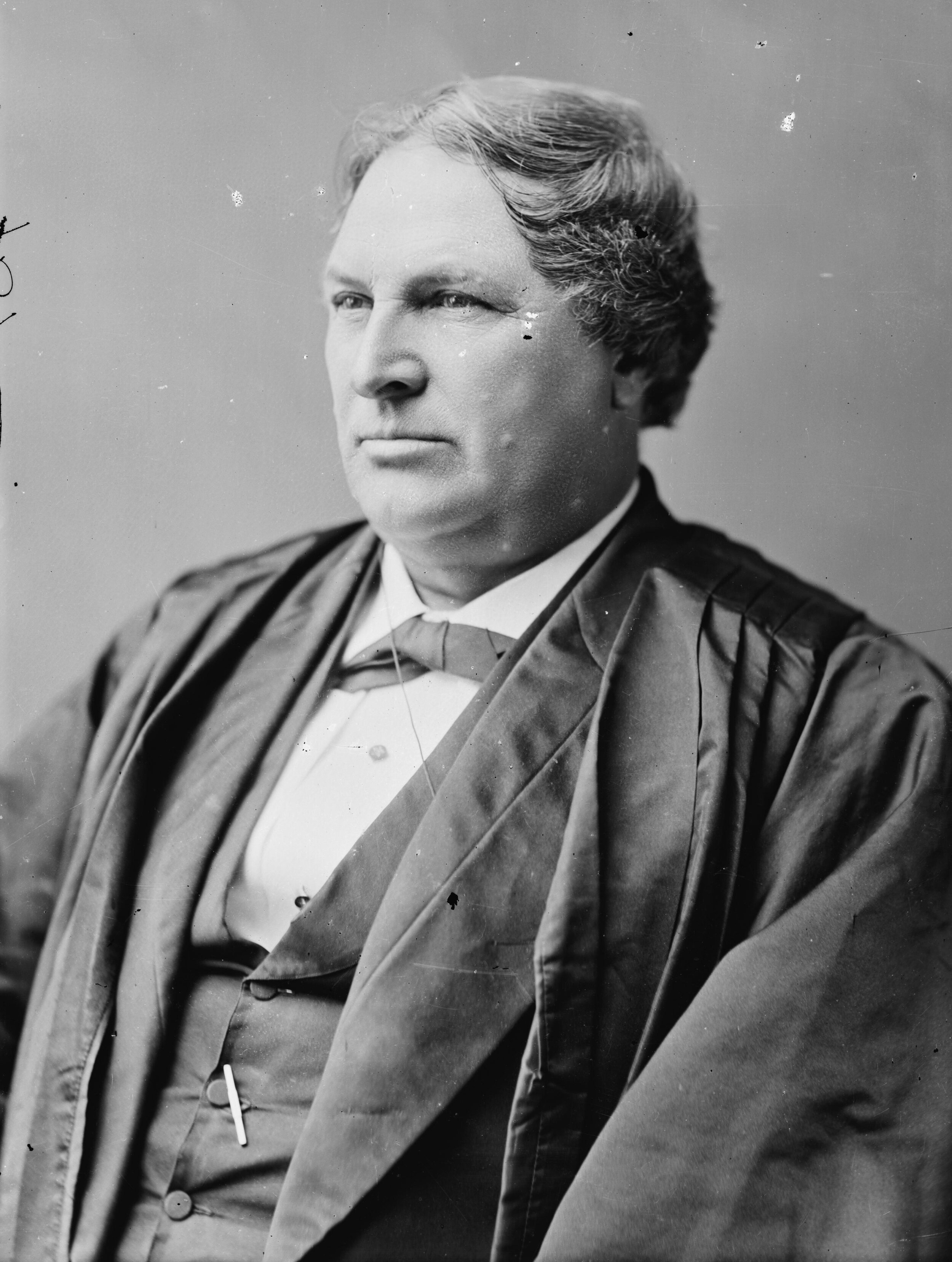

Ward Hunt

Ward Hunt

The least likely judge to side with the Minors’ interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment was Justice Ward Hunt. He was still relatively new to the Supreme Court when the Minors presented their case, but his stance on female suffrage was nationally known. Until 1901, each Supreme Court justice was required to ride circuit, meaning they traveled to one of thirteen different circuit courts of appeals to hear cases individually before they reached the Supreme Court. As the justice overseeing New York, one of Ward’s first assignments was to oversee the Susan B. Anthony trial. Yes. He was that judge. His dubious conduct during and after that trial, and the great lengths he went to keep Anthony’s trial from reaching the Supreme Court, were well known. It is extremely doubtful the Minors had any confidence Justice Hunt would decide in their favor, but they only needed five of the men to agree with the connection between citizenship and suffrage. Were there enough votes out there to get over the finish line?

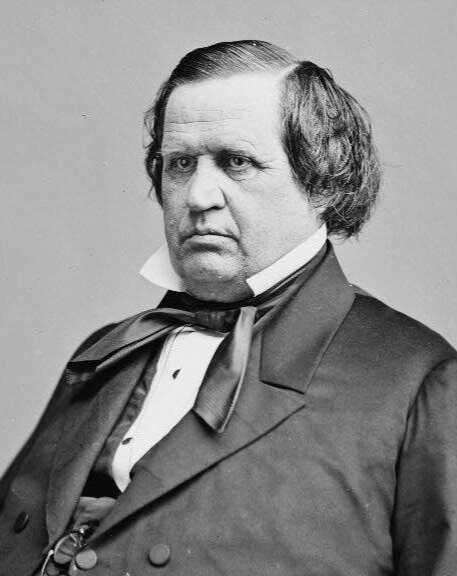

Samuel Miller

Two court cases decided in 1873 were the best indication of what the Minors could expect from the majority of the other justices. The first were the Slaughterhouse Cases and the second was Bradwell v. Illinois. These were the first cases exploring how the Fourteenth Amendment impacted the rights and privileges of citizenship, and the Supreme Court, as could have been expected, used a very narrow definition of citizenship to come to their decisions. Justice Samuel Freeman Miller wrote both judgments.

Samuel Miller

The Slaughterhouse Cases involved a Louisiana law that gave the Crescent City Live-stock Landing and Slaughter-House Company a charter to run the animal slaughtering in New Orleans and shut down all the other slaughterhouses in the area. A group of local butchers sued, saying the state monopoly was in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment as it abridged their privileges and immunities, deprived them of liberty and property without due process and denied them equal protection of the laws. The court did not agree, but only on a five to four vote that citizenship did not guarantee a right to a livelihood. There were only a limited amount of rights actually protected by the Constitution, and they were not about to interpret the Fourteenth Amendment along any other lines beyond its original intent.

Myra Bradwell

Bradwell v. Illinois was similar in many regards, but held one key difference: Myra Bradwell was a woman. Bradwell had applied to the Illinois bar, the Illinois Supreme Court refused to admit her, arguing, “God designed the sexes to occupy different spheres of action, and that it belonged to men to make, apply, and execute the laws, was regarded as an almost axiomatic truth.” Bradwell brought her case to the Supreme Court, arguing, as the butchers had, that her right to chose her profession had been taken. And, just as the butchers would learn, this court was not about to open any doors to interpreting the Constitution that they weren’t willing to have the country walk through. If Justice Miller couldn’t accept the butchers or Myra Bradwell’s idea of what the Fourteenth Amendment could be, it was doubtful he’d accept the Minors’ either.

Nathan Clifford

Nathan Clifford

Nathan Clifford was the lone Supreme Court justice hearing the Minor case placed on the bench before the Civil War. (Fun Fact: His great-great grandmother, Ann Smith, as a ten year old had accused Eunice, “Goody” Cole as a witch in 1672.) The last holdover from a different era when Democrats filled the bench and ensured slavery marched across the land, he wasn’t about to stir the waters. If the others voted against Minor, he certainly wasn’t going to argue otherwise.

David Davis

David Davis

Justice David Davis was well known for his independent streak. He had agreed with Justice Miller in the Slaughterhouse and Bradwell cases, believing it was not the place of the Supreme Court to add extra rights and privileges not spelled out explicitly in the Constitution. Around the time of the Minor case, Davis wrote a letter describing an encounter with “Mrs Wells – the new wife of Mr Wells, a bachelor of (45) who came to Danville in 1835 & staid there until ’45- He married to in Utica- His wife is a blue stocking, talks learnedly – loves to talk of knowing great men &c- - She is not to my taste - don’t love nor admire too learned women.” It was hard to imagine Justice Davis would be that impressed with the learned and sophisticated Virginia Minor.

Stephen Field

Stephen Field

As important as the Slaughterhouse Cases were, only five justices had agreed the butchers right to choose one’s profession was not a constitutional right. Four justices felt differently, and they all signed on to a dissenting opinion penned by the eccentric Justice Stephen Field. (Fun Fact: Field’s mother was named Submit, and he had done nothing in his decade on the Supreme Court that would indicate he saw any irony in her name.) Field argued that the Fourteenth Amendment was more than just about the freed slaves and needed to be interpreted more widely. While the Supreme Court would agree with Field years later, in 1875 the majority of justices seemed settled that the new additions to the constitution were not to be expanded upon.

Joseph Bradley

Joseph Bradley

While the Slaughterhouse Cases were decided on a slim five to four vote, the Bradwell Case was determined by a vote of eight to one. Both cases asked whether the right to choose a profession was constitutionally protected, which meant that three judges believed male butchers should have the right to choose their profession, but female lawyers should not. As such, Justice Joseph Philo Bradley felt the need to write a concurring opinion explaining why they had come to such different opinions on the same topic. Bradley dissented in the Slaughterhouse Cases, arguing that "the right of any citizen to follow whatever lawful employment he chooses to adopt… is one of his most valuable rights, and one which the legislature of a State cannot invade, whether restrained by its own constitution or not." And yet, in the Bradwell case, Bradley wrote:

“The civil law, as well as nature herself, has always recognized a wide difference in the respective spheres and destinies of man and woman. Man is, or should be, woman's protector and defender. The natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life. The Constitution of the family organization, which is founded in the divine ordinance as well as in the nature of things, indicates the domestic sphere as that which properly belongs to the domain and functions of womanhood…

The paramount destiny and mission of woman are to fulfill the noble and benign offices of wife and mother. This is the law of the Creator…In my opinion, in view of the peculiar characteristics, destiny, and mission of woman, it is within the province of the legislature to ordain what offices, positions, and callings shall be filled and discharged by men, and shall receive the benefit of those energies and responsibilities, and that decision and firmness which are presumed to predominate in the sterner sex. For these reasons, I think that the laws of Illinois now complained of are not obnoxious to the charge of abridging any of the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States.”

After penning such an opinion, based not on the United States Constitution but on a strange understanding of a ‘Constitution of the family,” coupled with English Common Law, strongly held misogynistic beliefs, the religious ideals of the day and a strict devotion to the patriarchy, it was nearly impossible to believe Justice Bradley could come down on the side of female suffrage. His was most certainly a vote against the Minors.

Noah Swayne

Noah Swayne

Justice Noah Haynes Swayne, the first of Lincoln’s five appointments, generally sided with the majority and rarely wrote any opinions. In the Slaughterhouse Cases he sided with Field, stating he felt the Fourteenth Amendment gave the butchers the right to their own living, but he agreed with Bradley in Bradwell that women did not. Like Justice Clifford, he was rarely a swing vote and rarely stepped out of the strict Constitutional framework he worked within. He certainly wasn’t going to stand up for this, of all causes.

William Strong

William Strong

Justice William Strong signed his name along with Justices Bradley and Swayne in the Bradwell opinion, agreeing that men had the right to control their livelihoods while women did not. There was nothing in his history to suggest he might vote in favor of reinterpreting the privileges that came with citizenship in a way that would include female suffrage.

Morrison Waite

Morrison Waite

With eight Supreme Court justices who had already demonstrated they would protect and prop up the patriarchy, even if it came to extralegal means or a reliance on traditional roles to exclude women from the rights and privileges they believed only men should have, the only chance the Minors had left was with Chief Justice Morrison Remick Waite. Waite had replaced Salmon P. Chase, the last Chief Justice, who had passed away shortly after becoming the lone dissenting vote in the Bradwell case. Chase had swerved from his traditional judgments regarding Bradwell and, while a minority of one, had demonstrated that he was not entirely opposed to the notion of women gaining more rights in society. With Chase’s death, the only slim hope the Minors had was gone as well. And unfortunately, the new Chief Justice’s name held within it everything the women’s rights movement of the time understood the situation to be.

Waite.

The women would have to Waite.

Minor v. Happersett

The Supreme Court Justices that decided the Minor v. Happersett case

The majority opinion of Chief Justice Waite was published on March 29, 1875. It was a lengthy diatribe, compiling a list of laws, traditions and customs to explain how the nine Supreme Court justices came to the conclusion that suffrage was not a condition of citizenship. The Supreme Court, comprised of middle aged white men of varying faiths, political persuasions, socio-economic backgrounds, and regional originations, had come together under the umbrella of the patriarchy in a nine to zero vote to keep women from voting. The following highlights from Chief Justice Waite’s opinion show the mindset of the court regarding the threads that bound citizenship, gender and suffrage and the threats they believed might pull the whole thing apart. To read the entire decision, click here: Minor v. Happersett.

“The question is presented in this case, whether, since the adoption of the fourteenth amendment, a woman, who is a citizen of the United States and of the State of Missouri, is a voter in that State, notwithstanding the provision of the constitution and laws of the State, which confine the right of suffrage to men alone…There is no doubt that women may be citizens… Sex has never been made one of the elements of citizenship in the United States. In this respect men have never had an advantage over women…. In this particular, therefore, the rights of Mrs. Minor do not depend upon the amendment. She has always been a citizen from her birth, and entitled to all the privileges and immunities of citizenship. The amendment prohibited the State, of which she is a citizen, from abridging any of her privileges and immunities as a citizen of the United States; but it did not confer citizenship on her. That she had before its adoption.

If the right of suffrage is one of the necessary privileges of a citizen of the United States, then the constitution and laws of Missouri confining it to men are in violation of the Constitution of the United States, as amended, and consequently void. The direct question is, therefore, presented whether all citizens are necessarily voters… In this condition of the law in respect to suffrage in the several States it cannot for a moment be doubted that if it had been intended to make all citizens of the United States voters, the framers of the Constitution would not have left it to implication. So important a change in the condition of citizenship as it actually existed, if intended, would have been expressly declared.

As has been seen, all the citizens of the States were not invested with the right of suffrage. In all, save perhaps New Jersey, this right was only bestowed upon men and not upon all of them. Women were excluded from suffrage in nearly all the States by the express provision of their constitutions and laws. If suffrage was intended to be included within its obligations, language better adapted to express that intent would most certainly have been employed… No new State has ever been admitted to the Union which has conferred the right of suffrage upon women, and this has never been considered a valid objection to her admission. On the contrary, as is claimed in the argument, the right of suffrage was withdrawn from women as early as 1807 in the State of New Jersey, without any attempt to obtain the interference of the United States to prevent it.

Certainly, if the courts can consider any question settled, this is one. For nearly ninety years the people have acted upon the idea that the Constitution, when it conferred citizenship, did not necessarily confer the right of suffrage. If uniform practice long continued can settle the construction of so important an instrument as the Constitution of the United States confessedly is, most certainly it has been done here… Being unanimously of the opinion that the Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon any one, and that the constitutions and laws of the several States which commit that important trust to men alone are not necessarily void, we

AFFIRM THE JUDGMENT.”

Ramifications and Conclusions

In the end, the Minors never really had a chance.

They must have known this, but still, what other choice did they have? They had to hope somehow that these nine men had it within them to interpret the Constitution neither through their own myopic and misogynistic lenses, nor with the same sexist lenses of the Founding Fathers who created this governmental framework. They had to hope they could see female suffrage through the lenses of law and justice and equality. But there wasn’t a single judge on that bench who was about to side with the Minors. The result, crouched in the guise of state’s rights and a narrow interpretation of our country’s highest laws, was that citizenship did not mean you got to vote.

If citizenship did not contain the right of suffrage, that meant people could be kept from voting for all sorts of reasons. Poll taxes. Literacy tests. Voter identification laws. This meant states were under no obligation to allow anyone unwanted to vote, which meant the vast majority of citizens in America remained virtually represented. They would have no say in who lead them. Who decided if we went to war. Who decided what taxes to pay. Who was protected from mob violence. Who kept their children after a divorce. Who was incarcerated. Who was killed. An American Revolution to bring equality and a Civil War to bring freedom, and most Americans were still powerless to affect the things that mattered the most in their lives. One hundred years after the battles of Lexington and Concord, the rallying cry of no taxation without representation still fell on deaf ears.

And so, it might be tempting to place the Minor decision in among the Election of 1872 and the Susan B. Anthony trial and so much else from this time period as meaningless exercises. Nothing much changed as a result of these years, after all. And yet, nothing could be further from the truth with regards to the Minor case. If nothing else, the courts were now officially closed as a venue for women to petition for suffrage. Or, for that matter, really any satisfaction before the law at all. It wouldn’t be until 1908 in Muller v. Oregon that the Supreme Court would hear another case involving women, and by then every judge that had ruled on Minor v. Happersett was long dead. This court simply wasn’t going to hear any more cases involving suffrage. And so it became clear in the days after this decision was handed down that the only way women would win access to the vote on a national level was to change the Constitution.

It would take forty-five years of struggle, but eventually the Nineteenth Amendment became law and female citizens could no longer officially be kept from the ballot box. It was not the journey the national women’s rights movement of the eighteen hundreds had hoped for, but eventually women took this vital right for themselves after fighting against a system that had every advantage and no desire to give even one bit of its power away. In a very real way, the Minor decision was an end to one journey but the beginning of another. More than that, though, it was a clear statement of what women were up against in their struggle and an indication of the struggle that still continues.

The decision in Minor v. Happersett stated clearly that citizenship does not confer suffrage. And so while the Nineteenth Amendment overturned this decision, it didn’t actually give suffrage to anyone, let alone women. It merely stated that one’s gender couldn’t be used to take voting from a citizen. There are still hundreds of ways to keep women from voting. Physical intimidation, traditional social norms, placing barriers to get to polling places, the need for government identification, being a convicted felon, and on and on. Every state except North Dakota requires citizens to register to vote, and most require further steps to vote. Until Minor v. Happersett is overturned, and the Supreme Court agrees with Virginia and Francis that suffrage is right and privilege of citizenship, and not something to be earned or taken away, millions of American citizens will continue to be disenfranchised. .

And so while the end result of Minor v. Happersett is not a happy one, it is worth remembering as the beginning of the long crusade that lead eventually to the Nineteenth Amendment and perhaps, someday, to the understanding that all citizens in our nation deserve actual representation instead of virtual representation. We’ve come a long way.

We still have so far to go.